Content Warning: This article, or pages it links to, contains graphic information about a harmful practice and/or violence.

February 2019 – In 2003, the United Nations named February 6 of each year the International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C), although the fight against the practice has a much longer history. On this day of recognition, the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) lead the way in what becomes a day full of campaigns, talks and conferences aimed at standing up for girls and ending the harmful practice.

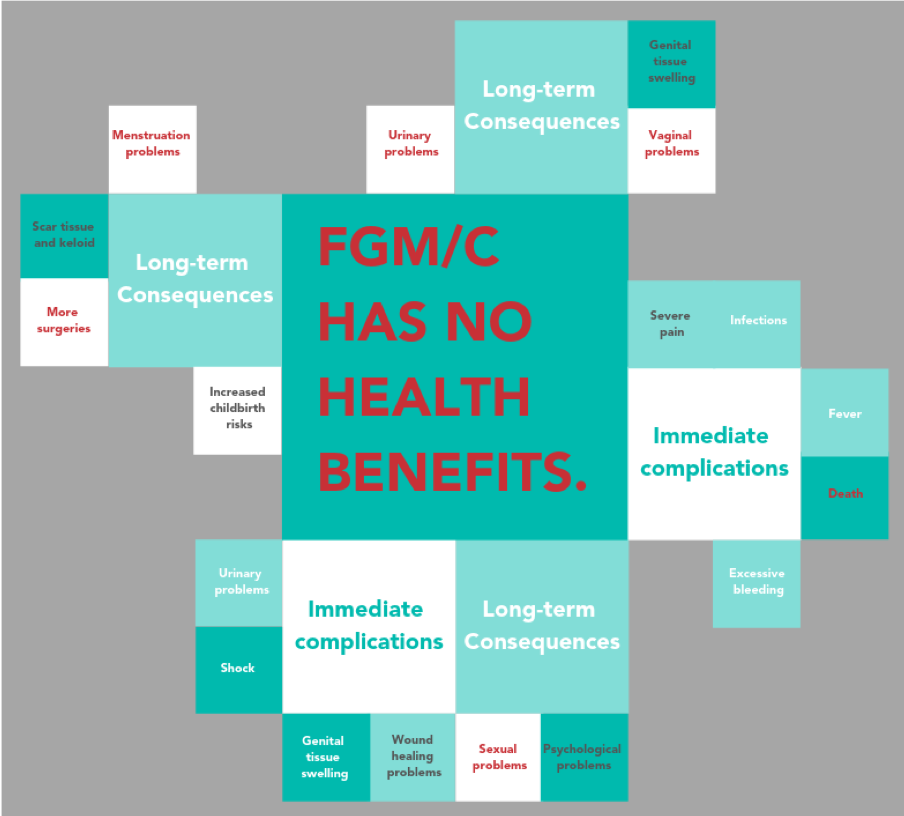

FGM/C refers to any procedures that intentionally alter or cause injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. The World Health Organization (WHO) categorizes four different types of such procedures: clitoridectomy, excision, infibulation and all other harms. Though the definition of the practice is agreed upon, its geographic and sociocultural underpinnings make it a much more complicated and controversial issue.

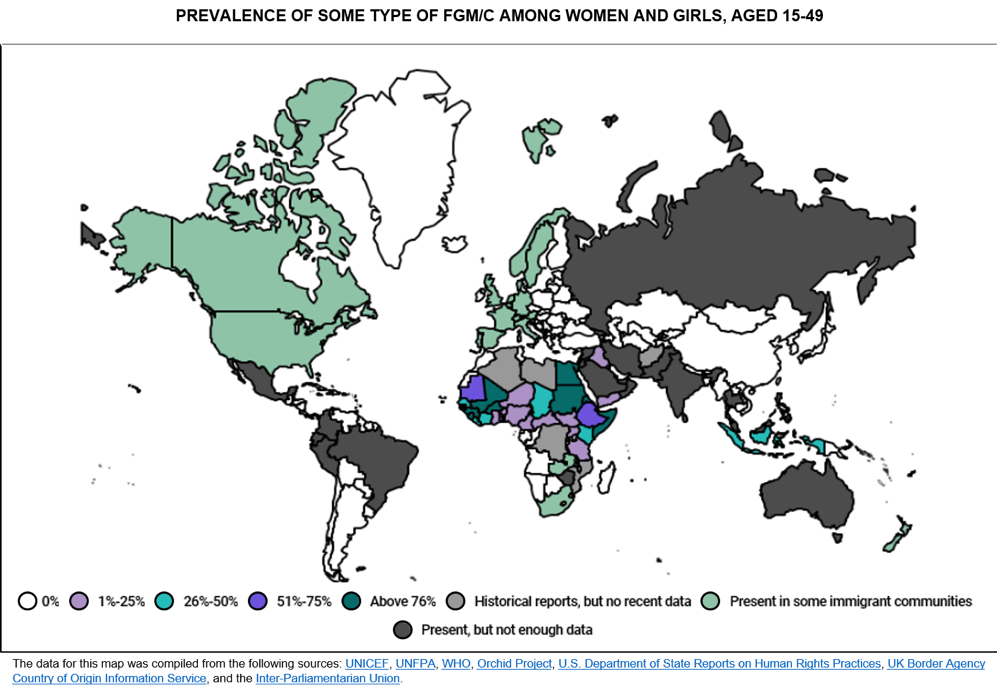

While predominantly present in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, there are FGM/C cases in every other region of the world, some stemming from deep-seated local traditions and others occurring in migrant communities. At the moment, it is estimated that more than 200 million girls and women alive have been cut.

The origination of FGM/C is highly debated. Some evidence from examinations on mummies suggests women of higher status in Pharaonic-era Egypt were cut. Other records from Victorian England and the United States in as late as the 1950s show that FGM/C was used to treat women with psychological disorders. This far-ranging data implies that the practice is deeply embedded in culture and notions of female roles and identity.

As such, the specific motivations behind FGM/C vary around the world, yet many families or communities support the practice because they have been led to believe it helps secure a positive future for their girls. Among the Kikuyu people of Kenya, for instance, FGM/C ceremonies are an initiation into womanhood, and girls that do not participate are considered children and cannot marry. As another example, the Yoruba people of Nigeria believe that if the baby’s head touches the tip of the mother’s clitoris during birth, the child will die. In Mali, some people believe women are prone to promiscuity and that FGM/C is a way to ensure virginity for marriage and loyalty thereafter. In Arab Sudan, an open vagina is considered unclean and impure, so infibulation is a way to “clean” and “purify” it. These beliefs, however, are typically built upon generations of deeply ingrained traditions and/or false information, rather than with the understanding of how harmful many of FGM/C’s consequences can be.

Though the WHO originally approached the issue with a culture relativism perspective, it declared the practice a universal major health concern in 1982. Since then, there have been multiple approaches to addressing FGM/C around the world. Advocates carried out several educational campaigns with the assumption that once people learned about the severe medical complications of FGM/C, they would not do it anymore. Yet, for many people, the social costs posed by not cutting girls outweighed what they understood to be the health risks, and inadvertently led to the practice being medicalized; doctors began to perform FGM/C in hospitals or nurses would do it during their time off work.

Furthermore, when the practice was reframed with the onset of the women’s human rights movements, it was called a tool of the patriarchy and a symbol of women’s oppression. This characterization divided people in the communities where FGM/C was practiced and the efforts to end FGM/C were denounced as being from a Western imperialist worldview. That is, efforts to stop FGM/C were denounced until women and leaders in those same communities began to condemn FGM/C too. Altogether, this pressure propelled many countries in the world to pass national legislation banning the practice by the end of the 1990s.

Though early efforts to end FGM/C were not as successful, they did identify three characteristics that future programs would need:

- they must be community-led;

- they should focus on changing social norms at the community, not the individual, level; and

- they should empower women to spearhead the change.

Today, the efforts to end FGM/C have survivors at their core, with numerous activists, NGOs, medical professionals and religious leaders coming together unanimously in that the practice needs to end.

At Vital Voices, our work is informed by these lessons. Under our Voices Against Violence Initiative, we fight to end FGM/C by engaging with multisector, multidisciplinary partners, including religious leaders, journalists, activists, NGOs, government officials, youth, men and boys. We have implemented programs with delegations from five countries in West Africa (Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Sierra Leone and Gambia), focusing on passing and/or implementing legislative reforms, engaging governments and media, developing national and regional networks of groups focused on the issue, and providing organizational capacity building and leadership development. We have worked with Dr. Morissanda Kouyaté, Executive Director of the Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices (IAC); the Global Media Campaign; Jaha Dukureh and her organization Safe Hands for Girls, The Big Sisters Movement and other activists working to end the harmful practice. We have also carried out research on FGM/C in Indonesia and Malaysia.

Even though efforts are more informed now than ever before, more than 3 million girls are estimated to be at risk for FGM/C annually. That is why it is crucial that not only today, but every day, we continue our work to end FGM/C by raising awareness and supporting those that are on the ground fighting for our girls. There must be zero tolerance for female genital mutilation/cutting.

This piece was authored by Daniela Mora Savović.